- Home

- Matt Kennard

Irregular Army

Irregular Army Read online

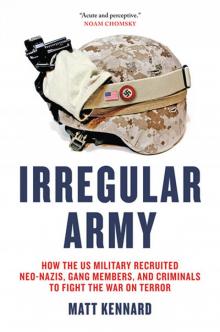

IRREGULAR

ARMY

How the US Military Recruited Neo-Nazis, Gang

Members and Criminals to Fight the War on Terror

Matt Kennard

First published by Verso 2012

© Matt Kennard 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-84467-905-8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kennard, Matt.

Irregular army : how the US military recruited Neo-Nazis, gangs, and criminals to fight the war on terror / Matt Kennard.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-84467-880-8 (hbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-84467-905-8 (ebook)

1. United States—Armed Forces—Enlisting, recruiting, etc.—Standards. 2. United States—Armed Forces—Enlisting, recruiting, etc.—Corrupt practices. 3. Soldiers—Health and hygiene—United States—Standards. 4. Physical fitness—United

States—Standards. 5. Soldiers—Alcohol use—United States. 6. Soldiers—Drug

use—United States. 7. Gang members—United States. I. Title.

UB333K46 2012

956.7044’34—dc23

2012018558

For all the people whose lives have been ended

or brutalized by these wars

An Army raised without proper regard to the choice of its recruits was never yet made good by length of time; and we are now convinced by fatal experience that this is the source of all our misfortunes.

Flavius Vegetius Renatus, in his military manual

De Re Militari, fifth century, as the decline

of the Roman Empire began in earnest

He served up our great military a huge bowl of chicken feces, and ever since then, our military and our country have been trying to turn this bowl into chicken salad.

Retired General John Batiste, former

commander of the First Infantry division in

Iraq, on Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, 2006

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Breaking Down

1 The Other “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”

Hitler in Iraq

Straight Outta Baghdad

War Criminals

2 Sick, Addicted, and Forsaken

Sippin’ on Gin and Hajji Juice

Collateral Damage Comes Home

3 Plump, Young, Dumb—and Ready to Serve

The Baghdad Bulge

Intelligence Ops

Child Soldiers

Grandpa Goes to War

4 Outsiders

Green Card Soldiers

Ask, Tell

Epilogue: Indiscriminate Trust

Notes

Index

Photo insert

Acknowledgments

This is my first book and it spent a long time germinating before it was finally written. Because of that there are lots of people all over the world who helped me make it real as I worked to focus the issues involved. There are two people particularly without whom this book would have been impossible. Jason Yarn helped me put the idea together from its tentative beginnings with great patience and kindness, while Max Ajl gave his time and skills selflessly at the start of the project. Lionel Barber, David Crouch, and Jo Rollo at the Financial Times were generous and understanding when I needed time to write.

Most thanks and love to my parents, Judy and Peter, for teaching me always to stand up for what you believe in and in turn believing in both this project and me. In their own different ways, they have dedicated their whole lives to trying to make the world a better place—they are my inspiration. Ana for her love, being the best editor and kindest person too, and more than anyone else making this book what it is. Thanks to my brother Daniel for his unwavering belief that I could do anything I set out to do. My grandma Mary has been steadfast in her support and love all my life—I couldn’t have done this without her. Thanks, Nan. Back when this was a seed of an idea Gizem helped me nurture it and was a voice I turned to throughout for sound advice.

Many thanks also to Andrew Hsiao at Verso for his insights into the topic and support throughout the process. Tariq Ali likewise showed faith in the project early on, while Tim Clark improved the final product immeasurably with his stellar editing. The guidance and wisdom of Beech was a constant support the whole way, alongside Rab whose intellectual truculence has taught me a lot over the years. The project started at Columbia University Journalism School where I was taught by Sheila Coronel, who afforded me the financial and intellectual support at the beginning when I was still staring at a blank page. The Nation Institute deserve huge thanks for giving me the financial and moral support needed to continue the initial story—democracy and journalism around the world would be hugely improved if every country could have an institution like the Institute. Salon published the first short story which gave birth to this book, so thanks to them and in particular Kevin Berger. There are also those who have kept me sane and laughing while writing, so thanks to: Tom, Nick T., Dave, Jake, Pilar, Steve, Frankie, Patrick, Declan, Billy, Whybrow, Al D., Shane, Ivor, Adam, Lex, Summer, Eugene, Jack, Laurence, Harry, Charlie, Chris, Leah, Ralph, Camilla, Hugh, Lucy, Suey, William, and Shannon.

War is the most traumatic event a human being can experience. That goes for those attacked and for those individuals sent to do the attacking. I would like to thank all the veterans who have come home and dedicated their post-combat lives to stopping these wars and fighting for the health and educational benefits that are rightfully theirs. This book is not an indictment of all US service members; it is an indictment of the people who sent them to war on the basis of a lie and knowingly allowed the whole institution to unravel.

It goes without saying none of the people above are responsible for what I have written.

Introduction: Breaking Down

I just can’t imagine someone looking at the United States armed forces today and suggesting that they are close to breaking.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, 20061

On September 10, 2001, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld stood in front of the assembled great and good of the Pentagon and delivered an expansive lecture entitled Bureaucracy to Battlefield.2 Its prescriptions were extremely radical—among the most portentous in US military history—but thanks to the terrorist atrocities the following day his words remain buried deep in the memory hole, while their consequences are buried under the sands of Iraq and Afghanistan. “The topic today is an adversary that poses a threat, a serious threat, to the security of the United States of America,” Rumsfeld began, before revealing the threat to be not Al-Qaeda, but the “Pentagon bureaucracy.” “Not the people, but the processes,” he added reassuringly. “Not the civilians, but the systems. Not the men and women in uniform, but the uniformity of thought and action that we too often impose on them.” In essence, Rumsfeld’s speech that day was designed to lay the ground and soften up his workers for a massive privatization of the Department of Defense’s services. It was the realization of a long-held dream for Republican politicians and their corporate allies in Washington—who would now be presented with a sweet shop full of lucrative government contracts to chew on. With the tragic events of the next day and the ensuing two-front ground war in the Middle East, Rumsfeld was gifted the perfect opportunity t

o enact his program with minimal opposition. The results were clear eight years into the War on Terror when the DOD (Department of Defense) had 95,461 private contractors working for them in Iraq compared to 95,900 US military personnel.3 The use of private contractors was by then so embedded that Barack Obama’s initial skepticism about their use displayed while a senator became one more item in a long list of policy climbdowns. But while the privatization of the war effort is a topic that has been explored extensively by a number of journalists, notably Jeremy Scahill,4 one aspect of the program has received little coverage—namely Rumsfeld’s plan for soldiers on the payroll of the DOD. Equally radical, it was a scheme that would prove catastrophic for the troops and the occupied populations living under them. Veiled in the language of business-style efficiency savings, Rumsfeld’s plan was intended to eviscerate the US military, which was to become merely an appendage to the massive private forces the US would employ in the future.

“In this period of limited funds,” he continued, “we need every nickel, every good idea, every innovation, every effort to help modernize and transform the US military.”

This could only be done by changing the basics of how the Pentagon worked, in a process that would later be dubbed “Transformation”: “Many of the skills we most require are also in high demand in the private sector, as all of you know. To compete, we need to bring the Department of Defense the human resources practices that have already transformed the private sector.” Even the DOD itself was to be run like a corporation: “We must employ the tools of modern business. More flexible compensation packages, modern recruiting techniques and better training.” What Rumsfeld desired was a scaled-down, streamlined US military—a reversal of what had become known as the Powell Doctrine, named for the Desert Storm general Colin Powell, who believed in high troop numbers, “overwhelming force,” and a defined exit strategy. It was a risky approach for Rumsfeld to take. Even before 9/11, Powell, by now Secretary of State, had observed that “our armed forces are stretched rather thin, and there is a limit to how many of these deployments we can sustain.”5 That would prove to be an understatement. But Rumsfeld was backed in his new approach by his boss, President George W. Bush, who much to Powell’s consternation shared the same vision. “Building tomorrow’s force is not going to be easy. Changing the direction of our military is like changing the course of a mighty ship,” Bush said in May 2001.6

The oft-repeated cliché is that everything changed on September 11, and indeed it did for millions of Americans. But not for Rumsfeld: his priorities stayed the same while his popularity surged after he was pictured helping victims of the attack at the Pentagon into ambulances. He now had not only the ultimate cover for changing the course of the mighty ship and designing a pared-down business-style war machine, but also the perfect laboratory for his experiments. The war drums began beating in earnest soon after 9/11. The invasion of Afghanistan began with a Rumsfeld-inspired Special Forces mission to bribe local warlords, supported by airstrikes obviating the need for “overwhelming” manpower. But the so-called neoconservatives weren’t finished yet: they had their eyes on the ultimate prize of Iraq and, sure enough, eighteen months later and much more controversially, the country with the third-largest reserves of oil in the world was attacked—a move Rumsfeld’s deputy Paul Wolfowitz had been advocating (again, with a Rumsfeld-style small force) in the 1990s. Over the next decade, US bombs fell on Syria and Pakistan and Yemen, among others, as the Middle East turned into a conflagration of Dantesque proportions, with civilians, insurgents, and US service members all caught up in the blaze.

Rumsfeld’s guinea pigs for his new experiment in “flexible” military planning were the patriotic Americans who believed they were signing up to defend their country—at the height of the War on Terror, 1.6 million of them had served in the Middle East.7 That number, equivalent to the population of a country like Estonia or a city like Philadelphia, must have come as a surprise to Rumsfeld, who had predicated his whole war plan on a much smaller force and a short war. In fact, soon after 9/11, General Tommy Franks had been asked by Rumsfeld to estimate how many troops an invasion of Iraq would require. The last contingency plan for invading Iraq, dating from 1998, had recommended a force of more than 380,000. But, apparently under pressure from Rumsfeld, General Franks presented his “Generated Start” plan with an initial troop count of just 275,000.8 Even that was too much for Rumsfeld, who in typical peremptory fashion slapped down the general and pushed for an even smaller force. According to Michael Gordon, military correspondent for the New York Times, “They came up with a variant called the running start, where you begin maybe with a division or so, and then the reinforcements would flow behind it. So, you start small but you just keep sending more of what you need.”9 This approach generated what was called a “war within a war,” as it pitted Rumsfeld against General Eric Shinseki, the army’s popular Chief of Staff, and Secretary of State Powell, both of whom (rightly) believed that large numbers of troops would be needed to ensure security after the initial fighting was over. General Shinseki publicly proposed a force of 200,000, after his frustration with Rumsfeld’s intransigence on the issue became insufferable.10 It didn’t matter. Rumsfeld wouldn’t listen.

This tactic was so blinded by ideology that it directly contradicted the ostensible goals of the invasion—disarming Saddam Hussein. “The United States did not have nearly enough troops to secure the hundreds of suspected WMD sites that had supposedly been identified in Iraq or to secure the nation’s long, porous borders,” said Michael Gordon and General Bernard Trainor in their book Cobra II. “Had the Iraqis possessed WMD and terrorist groups been prevalent in Iraq as the Bush administration so loudly asserted, [the limited number of] U.S. forces might well have failed to prevent the WMD from being spirited out of the country and falling into the hands of the dark forces the administration had declared war against.”11 But it wasn’t just ideology that was to blame for the ensuing damage to the US military and its war aims; there was a sizeable dose of incompetence as well. Declassified war-planning documents from the US Central Command in August 2002 show how ill-prepared the Bush administration was for the occupation which was to follow. The plan they put together assumed that by December 2006 the US military would be almost completely drawn down from Iraq, leaving a residual force of just 5,000 troops.12 It was madness, but nevertheless music to Rumsfeld’s ears.

After much wrangling, Rumsfeld and Franks compromised and the initial force numbered 130,000, much smaller than had been envisioned in the 1990s, but not as slim as Rumsfeld had hoped. It didn’t go to plan anyway, and the troop levels were not enough to get a handle on this country of 30 million people. Incrementally more service members were sent out alongside private contractors as the situation descended into chaos after the first viceroy Paul Bremner’s decommissioning of the police and military sparked endless violence. By 2005, the US had 150,000 troops deployed in Iraq, and 19,500 in Afghanistan. But the war plan meant the military wasn’t prepared in any way for this kind of extended deployment—and it was unraveling. In 2005, just two years into the war in Iraq, people were talking openly about the fact that the US military had reached breaking point. At a Senate hearing in March of that year, General Richard A. Cody expressed these concerns publicly: “What keeps me awake at night is what will this all-volunteer force look like in 2007.”13 But he didn’t know the half of it. Worse was to come as in the same year the army missed its recruitment targets by the largest margin since 1979, a time when US society was still afflicted with so-called “Vietnam Syndrome” and the army was much bigger and recruiting twice as many soldiers.

Breaking Point

Around this time a retired army officer named Andrew F. Krepinevich, writing under a Pentagon contract, released a shocking report which was scathing about the US military being able to maintain its troop levels in Iraq without breaking the military or losing the war. His diagnosis was simple: the US armed forces were “confronted with a protracted d

eployment against irregular forces waging insurgencies,” but the ground forces required to provide stability and security in Afghanistan and Iraq “clearly exceed those available for the mission.”14 To compensate, the army was introducing change by the back door at the expense of their troops. Krepinevich pointed to the frequent and untimely redeployment of service members. “Soldiers and brigades are being deployed more frequently, and for longer periods, than what the Army believes is appropriate in order to attract and retain the number of soldiers necessary to maintain the size and quality of the force asking.”15 He offered three solutions for overcoming the desperate shortage of troops: redeploy existing troops more frequently still; redeploy them for even longer; or deploy US Marine ground troops. The first two of these prescriptions had already been undertaken by the army, but it was a dangerous game. “How often can a soldier be put in harm’s way and still desire to remain in the Army?” Krepinevich asked. “It is not clear, even to Army leaders, how long this practice can be sustained without inducing recruitment and retention problems.”16 His conclusions were not optimistic: the army, he said, was “in a race against time,” in which “its ability to execute long-term initiatives” was compromised by the “risk [of] ‘breaking’ the force in the form of a catastrophic decline in recruitment and retention.”17 He continued that it would be difficult not to stress the active and reserve components “so severely that recruiting and retention problems become so severe as to threaten the effectiveness of the force.”18 By now, then, everyone—including even Rumsfeld himself—knew the army had to increase in size. “With today’s demands placing such a high strain on our service members, it becomes more crucial than ever that we work to alleviate their burden,” said Representative Ike Skelton (D-MO), who had a long track record of advocating for a bigger army.19 But with recruitment down and anger at the war widespread how could this be done?

Irregular Army

Irregular Army